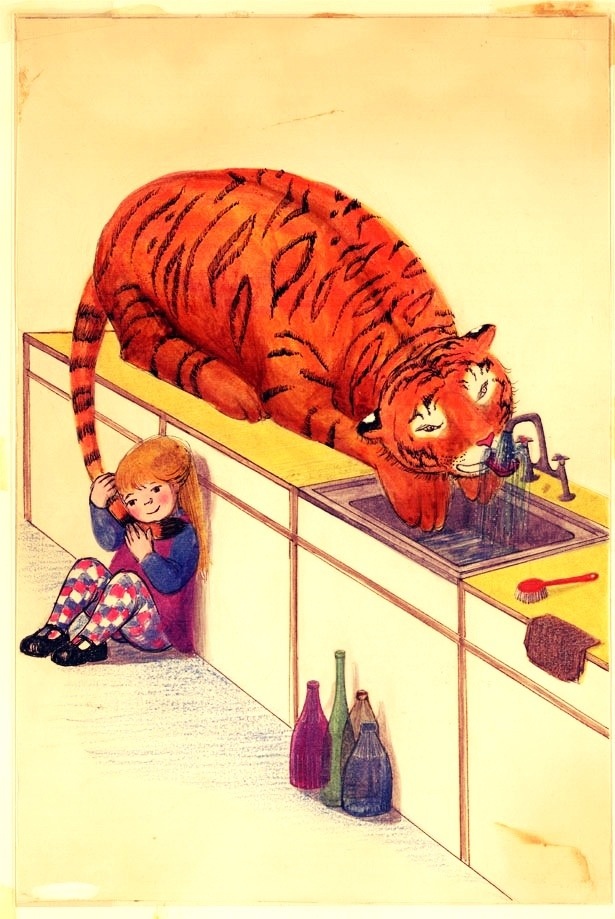

The Tiger

My mother called me. It was very important. “Sadie. You must, I repeat MUST watch that programme about the woman who wrote The Tiger Who Came To Tea. Deborah Carr. Not Deborah Carr. She was in the The King & I. What’s her…JUDITH. JUDITH KERR. That’s it. Anyway. She’s got a thing on the dooberry and it’s wonderful. Watch it. What an amazing woman.”

After promising I would, then having a general chinwag about Christmas lists and saucepans, we signed off – me promising again to watch the thing about the lady who wrote The Tiger Who Came To Tea. I got on with my day, but I was smiling at the memory of that book. I could see the pictures in my mind’s eye as I pottered about.

The story has stuck.

It was published in 1968 and it is still one of the best selling picture books of all time. It recently got made into a stage show, which was nominated for awards. I have read it to my nephew, I have read it to my niece. It is one of their favourites. It is still piled high in bookshops with an attendant range of merchandise. Children who could not tell you anything about 1968 could tell you the story of Sophie and the tiger.

There is something in the story.

I doubt we could even explain, really, why it is so loved. Was it the calmness of Sophie in being met by a normally ferocious beast? Was it the casual cheek of the tiger eating everything, drinking everything (even the contents of the tap!) and then sodding off? Was it the unquestioning complicity of the mother; her openness to the unexpected? Was it the father coming home in his traditional English hat, finding he had no tea, and coming up with the cracking solution to go to the caff for sausage and chips instead? Was it the inexplicable trumpet the tiger is playing on the final page, the letters G O O D B Y E wisping out of the end of the horn?

Was it something in the ordinary home greeting an extraordinary visitor; the juxtaposition of reality and magic that so captured the world?

I wonder if the Booker prize winner The Luminaries, with its 832 pages, will have such a loyal following forty years from now.

Stories are in our blood, our hearts, our minds, memories, imaginations, dreams, they are coursing through our sub-conscious. They are in the chats we have, the looks we give, the gossip we hear, the things we ignore. They shape us. We make our own, tell our own. We want to hear them, we swap them. We pay to be entertained by them in a staggering array of growing mediums. No hour of our day is without its story – even alone in a long bath or out walking or filling our basket in an empty supermarket, we are followed internally by snatches of story – true or imaginary – the filigrees of our amazing brains whirring away doing so much more than mechanising our day’s survival. If you see a young homeless person sitting beneath an ATM and you walk away to another bank, you are writing your own story – you paint an instant picture of them (their story), you choose your actions based on the stimulus (your story). If you pick up a dropped glove and place it on a railing for someone to find, if you ignore the doorbell, if you have an unexplained hankering to go to Papua New Guinea… They’re all little parts in little stories that could go anywhere.

I haven’t watched the programme about the nice lady who wrote The Tiger Who Came To Tea yet. Maybe I don’t want to know about Judith Kerr – her life, how she wrote, what aspects of her truth hide beneath the cloak of fiction in her stories.

Maybe I don’t want to spoil the magic. Maybe I still think the tiger might come back.